I’m currently pursuing my Diploma certification through the Wines & Spirits Education Trust, and the below is an exploration of the topic of branding in wine as part of the unit dedicated to the Global Business of Wine. Results are in (I passed with distinction!), so I’m happy to be able to share this here. Text and research are my own, and I’ve included sourcing as appropriate.

The Brief: Wine branding is important across the price spectrum from the likes of Blossom Hill to Château Lafite-Rothschild. Many in the industry strive to create and sustain wine brands but do consumers benefit from them as much as those who own them?

Branding is a huge force in global business, connecting a name, an image, and perhaps a concept intimately with a product in order to create a relationship with the end consumer, ultimately driving purchase intent. Within the context of wine, however, it is a nuanced subject due to the fact that wine is a living product and that much of its value, many argue, is intrinsically variable, with the product changing from vintage to vintage, place to place, and even over time in bottle. Yet creating a brand – and brand loyalty – is an integral part of selling a product, so producers large and small seek a variety of means of connecting their product to the consumer, especially in a field as fragmented and crowded as wine. This essay explores the unique challenges of branding in wine along with some successful attributes, specifically within the field of still light wines, and how the role of brands in wine affects the consumer.

Defining the Nuances of a Wine Brand

The purpose of a brand is to create familiarity with a consumer and to elicit a response, whether purchase or referral, thereby distinguishing it from its competitive set. The brand equity of the product’s identity defined through name and visual indicators like logos thus creates value for those selling the product, as “this value is reflected in both consumer loyalty and price premiums that consumers are willing to pay for a particular branded product.”[1] Said simply, brand value drives business, which is important for those creating and selling any product, including wine.

Wine branding is a wide field, encompassing a variety of themes from place of origin to grape to labeling, across a fragmented global distribution network and with limited supply in a given vintage. The difficulties of creating a truly international, widely available, consistent product is inherently difficult in wine, as noted in the Oxford Companion of Wine: “it can be even more difficult to maintain consistency of a product as variable as wine. Supplies are strictly limited to an annual batch production process. Wine cannot be manufactured to suit demand.”[2] In his analysis of the two cultures of wine, Jamie Goode from the website wine anorak defines these two types as “commodity” wines and “terroir” wines: “On the one hand we have wine as a commodity… As long as the quality is adequate and the price is right, [consumers] aren’t too worried about the source,” while on the other hand, there is wine that draws interest specifically because of its source material.[3] Within the larger topic of branding in wine, it is the commodity wine that we will further analyze, although we will return to the concept of the terroir wine in the final section of this paper when looking at the impact of brands on the consumer, and on consumer choice.

At any level, branding in wine matters for producers and retailers because strong brands are those that translate into sales at either end of the spectrum. Barefoot is the biggest selling mass brand of wine globally, with a total volume of 18 million 9l cases sold in 2014,[4] while in the more specialized, fine wine market, Chateau Margaux 1996 was the biggest seller that year, with more than £1.3 million of that one vintage sold, according Gary Boom MD of the Bordeaux Index.[5]

Defining Success & The Tools Needed to Make It Happen

Successful brands are both known and have followings – consumers that are either return buyers, in the case of many accessible brands, or aspirational consumers, in the case of well-known prestige brands. To varying degrees, the notion of a commodity product exists at all points along the price spectrum with wine, from mass-produced labels like Concha y Toro and Gallo’s Barefoot to more prestigious labels like Penfold’s Grange. What these wines have in common is consumer familiarity with the name and/or label, consistency in style and/or quality, accessibility, and a nuanced definition of place in the world.

Market research into consumer preferences has proved effective for the success of large, mass brands like Sutter Home: “In 2014 the company added “Red Blend”, a mix of Zinfandel, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, as its latest consumer crowd pleaser. This launch wasn’t just based on a hunch: Nielsen data shows that red blends are growing at twice the speed of Sauvignon Blanc in the US market and six times faster than the country’s overall wine category, making up 6% of total off-trade wine sales.”[6] Such brands meet the important criteria of familiarity and accessibility – Sutter Home popularized the category of White Zinfandel in the 1970s and is widely available in supermarkets throughout the US – and are actually looking to produce styles responding to consumer tastes.

For prestige brands, quality, history, and long-term consistency are often what matter. Looking at the great growths of Bordeaux, the 1855 Classification has long proved to be a huge branding mechanism for the 60 wines that were considered classed growths, essentially codifying their marketability at the high-end of the price spectrum ever since. The result has been a sense of exclusivity, which the brands themselves have cultivated; these are wine brands that deliver experiences, or the promise of them, that belong to a class apart. Bordeaux’s Lynch Bages is consistently ranked on the Liv-ex Power List; its brand strength is tied to the fact that the quality of the wine hasn’t waned in decades: “it’s a benchmark quality claret,” says Joss Fowler of UK Retailer Fine & Rare.[7]

One could consider these four pillars, as laid out by the Luxury Institute, in defining a premium wine brand: “superior quality, exclusivity, enhanced social status, and an overall superior consumption experience.”[8] Penfold’s Grange in fact was named the world’s most admired wine brand of 2015,[9] and it encompasses all of these various criteria for a successful, premium wine brand — it is considered “the flagship of the entire Australian wine industry… a true icon [but still] a branded wine, not tied down to a geographic locale and made to some sort of consistent style and quality each year.”[10] Indeed, the power of the great wine brands of Bordeaux falls within this context as well: superior yet still known, accessible, if only aspirationally. According to Liv-ex director Anthony Maxwell, their reputation and success stems from “the size of the properties in Bordeaux. That’s where there is volume, quality and price, and that’s what people can get behind… these are the wines that are most sought after reflected in value of total trade.”[11]

So accessibility for the consumer is key to building a brand, and the primary vehicle for raising awareness about what makes a brand desirable is communication. There is a strong relationship between brand names, pricing, and consumer purchasing habits, both on and off premise.[12] Communication is thus core to a successful brand strategy, and brands can reach consumers through a suite of marketing tools, including: advertising and PR, wine awards, reviews, social media, newsletters and websites, tasting rooms, sponsorships, direct-to-consumer channels, marketing within distribution networks, and visual indicators such as logos and labels. The internet in particular – whether through label-recognition apps, direct engagement opportunities on Facebook or via newsletters – has opened up “a number of ways in which to build brand awareness, enrich customer experience and stand out from the competition.”[13]

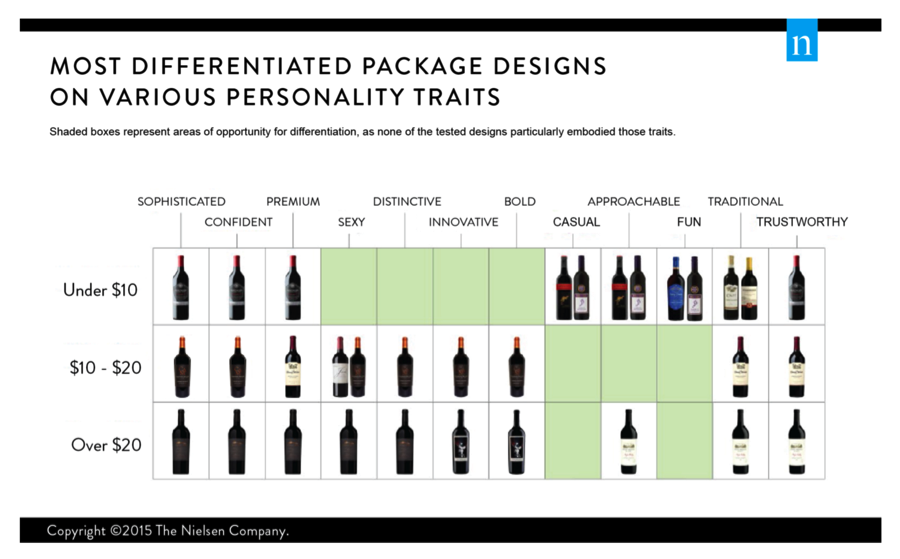

Of all of these tools, however, it is the label that has the most immediate impact on the consumer’s purchasing decision, given no previous experience with the brand: “There’s more competition than ever to capture the attention of U.S. consumers and more are looking at packaging and design as more than just protecting the quality of wine but attracting new customers and maintaining [their] existing,” notes Editor Jim Gordon of Wines and Vines,[14] and Nielsen reports that 64% of consumers will try a new product based on eye-catching packaging, with personality traits of the most attractive packaging varying along price scale (see Appendix A).[15] The importance of the label is illustrated by an example from Randall Grahm of Bonny Doon Vineyard, as he noted with his red blend Contra. Reputation and quality wine alone weren’t enough to make a wine a successful brand: “[Says Grahm] ‘It was a very good wine and got good reviews, but it wasn’t selling well … so we thought, oh, shoot, it’s got to be the label.’ […] Under its new wrap, the wine increased sales about 50 percent… ‘But it made one realize that the label is super crucial—you can’t get by with just good wine. You have to have good wine plus an attractive label at that price point.’”[16]

Advantages and Disadvantages of Wine Brands for Consumers

Wine brands can certainly simplify the understanding of and decision-making process surrounding wines to buy: “The wine market is a particularly crowded one and this adds to the complexity of wine purchase decisions for many consumers… This suggests that building a brand is very important in the wine market and that successful wine brand names stand out from competing brands.”[17] Damien Wilson, Hamel Chair in Wine Business at Sonoma State University, noted that there is a key difference between how the industry and consumers communicate about wine, essentially using different languages.[18] Well-known brands can help bridge this gap, connecting the consumer to stories, places, or even just lifestyles that they might want to emulate.

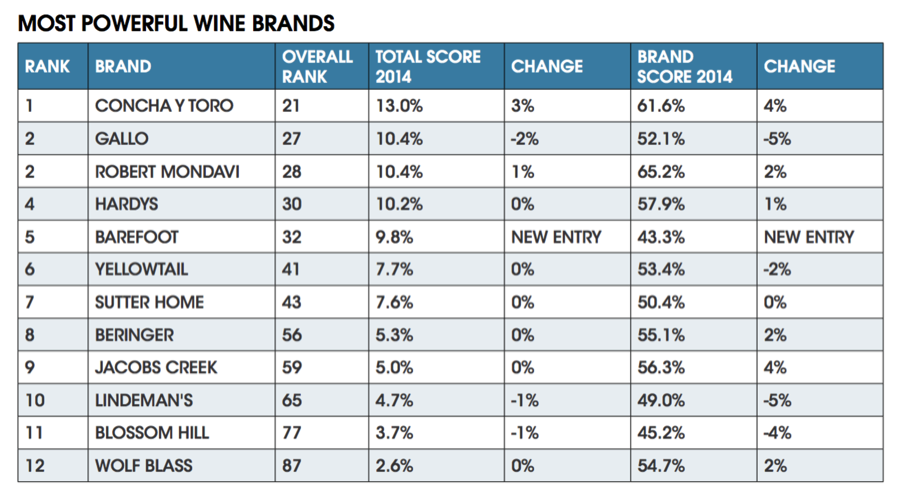

For wines on the lower end of the price spectrum, volume and consistency are key factors with regards to what wine brands are best known and thus most sold, including wine brands like Concha y Toro and Blossom Hill (see Appendix B),[19] but it’s also about their refreshing approach to branding and talking about wine that gets new consumers into the category. E&J Gallo vice-president Bill Roberts notes that many people are still “intimidated by wine… There are people who aspire to the sophistication of wine.” Indeed, of their top selling wine Barefoot, he noted, “About a third of consumers who purchase Barefoot are new to the category.”[20] And this is where mass, generic wine brands are most useful for consumers: a consistent, palatable, approachable commodity that customers can trust, offering “a familiar name that acts as a guarantee of consistency and quality.”[21]

However, according to many scholars, “one of the greatest dangers of modern enology is the standardization of wines as a result of overly systematic interventions and adjustments,”[22] which are often necessary for the production of a consistent, commodity product. And, especially as greater education surrounding wine increases, consumer interest is moving toward higher quality and greater authenticity,[23] and this global market of mass wine brands does not necessarily address this need.

This brings the conversation back to the question of “commodity” versus “terroir” wines introduced at the start of this essay. The wine sector is by nature fragmented, and while that represents major difficulties in getting through equally disjointed distribution networks, it is also integral to the integrity of wine that reflects heritage, region of origin, grape variety, and vintage – and educated consumers are increasingly expecting this from the wine they buy.[24] There is a place for the luxury wine brands to position themselves in this search for estate wines, as there is a much greater focus on quality and source material. Many great estates invoke a sort of “approximate authenticity” to cultivate a sense of what makes the wine unique, while professionalizing their systems to compete in the global marketplace: “It’s common for such wineries to appear to reject a market-orientation [and instead] follow an identity-driven approach that emphasizes producing wine true to the winery and the terroir.”[25]

However, limited production and geographical delineation are essentially inherent to winemaking, as historically many producers were working their own family plots, or even now, when many winemakers have deep relationships with the growers from whom they buy their grapes. Many worry that the rise of brands in wine, and their dominance at major retailers and in key on-premise placements, “means a loss of diversity for everyone. The rarer, more interesting wines can’t hope to compete in such a competitive multiple-dominated marketplace.”[26] So, while brands may help a consumer navigate in a sea of choices, are they really leading to better decisions? Or are they homogenizing the field of wine, as the smaller, terroir-driven producers work ever harder to compete for consumers’ attention, lost amongst the fragmented nature of the industry.

Conclusion

Wine branding has proved conclusively important in the growth of the sector, bringing in new customers into the consumption funnel at various points along the chain. Thus, from one perspective, if major branded wines can be used as a gateway, as has been suggested by multiple sources, before consumers switch “up” to higher quality wines, there is a marked advantage to ubiquitous branded wines in the marketplace, particularly at affordable price points. Furthering this argument, the existence of prestige brands also presents consumers with an additional, aspirational side to wine, a place to move to once they’ve gotten comfortable with the category. On the other hand, brands can have a detrimental impact on the industry as a whole, reducing the ability of smaller producers to compete and thus limiting consumers’ exposure to and awareness of the myriad of nuances that make the field of wine so interesting. Smaller wine companies must pay ever more attention to the marketing tools available to them, even on limited budgets, in order to gain share of wallet and share of cellar.

Whichever side of the argument one falls on, all together – label, placements, communication strategy – these brand components are integral to telling a story about the wine in the bottle, and the story is what ultimately brings the consumer into the world of wine. According to Milton Pedraza, CEO of the Luxury Institute, wine companies should look to “deliver beyond the product and create an experience that is focused on a great quality product with a compelling story and an experience that creates a long-term relationship,”[27] and this is true at all points along the spectrum of winemaking, regardless of price of the wine or size of the winery or wine brand.

Appendix A (Nielsen)

Appendix B (Power 100 Brands)

[1] Forbes, Sharon, and Dean, David. ” Consumer Perceptions of Wine Brand Names.” 7th AWBR International Conference June 12-15, 2013.

[2] Robinson, Jancis, and Julia Harding, MW. Oxford Companion of Wine, Sept. 2015.

[3] Goode, Jamie. “The Two Cultures: How the Rise of the Brands Is Changing the Face of Wine.” Wine Anorak.

[4] Stone, Gabriel. “TOP 10 WINE BRANDS 2015.” The Drinks Business.

[5] Bruce, Tom. “TOP 10 MOST POWERFUL FINE WINE BRANDS.” The Drinks Business.

[6] Stone.

[7] Bruce.

[8] King, Jen. “Younger Affluents with Higher Incomes More Willing to Pay for Fine Wines.” Luxury Daily: The News Leader in Luxury Marketing, 24 Mar. 2016.

[9] “Penfolds Crowned World’s Most Admired Wine Brand – Drinks International – The Global Choice for Drinks Buyers.” Drinks International. N.p., 4 Mar. 2016.

[10] Goode.

[11] Bruce.

[12] Forbes and Dean.

[13] Bartley, Kathie. “DOES YOUR WINE MARKETING STRATEGY TAKE ADVANTAGE OF NEW MEDIA OPPORTUNITIES AND TARGET EMERGING WINE CONSUMERS?” Kathie Bartley Wine Marketing. N.p., 16 July 2015.

[14] Bortolot, Lana. “Wine Label Designs: When What’s on the Outside Matters.” Weblog post. Nomacorc Industry Blog. Nomacorc.com, 19 Oct. 2015.

[15] “Wine Buyers Judge Bottles by Their Labels-How Can Brands Stand Out?” Nielsen, 17 Dec. 2015.

[16] Bortolot.

[17] Forbes and Dean.

[18] Haros, Reka. “Wine Branding: Why It’s Important for the Industry’s Growth.” Weblog post. Nomacorc Industry Blog. Nomacorc.com, 24 Nov. 2015.

[19] “The Power 100 The World’s Most Powerful Spirits & Wine Brands, 2014.”The Power 100. Intangible Business, 2014.

[20] Stone.

[21] Goode.

[22] Dominé, André. “Noble and Mass-Produced Wines.” Wine. N.p.: H.F.Ullmann, 2008. N. pag 117.

[23] Forbes and Dean.

[24] Dominé.

[25] Heine, Klaus, and Francine Espinoza Petersen. “Marketing Lessons Luxury Wine Brands Teach Us About Authenticity and Prestige.” The European Business Review. N.p., 19 Jan. 2015.

[26] Goode.

[27] King.

Bibliography

Adams, Andrew. “Making Your Wine Brand Stand Out.” Wines & Vines. N.p., 5 June 2015. Web. http://www.winesandvines.com/template.cfm?section=news&content=152521.

Bartley, Kathie. “THE POWER OF A GREAT WINE BRAND NAME.” Kathie Bartley Wine Marketing. N.p., 18 Apr. 2015. Web. http://www.kbwinemarketing.co.nz/wine-news/the-power-of-a-great-wine-brand-name/.

Bartley, Kathie. “DOES YOUR WINE MARKETING STRATEGY TAKE ADVANTAGE OF NEW MEDIA OPPORTUNITIES AND TARGET EMERGING WINE CONSUMERS?” Kathie Bartley Wine Marketing. N.p., 16 July 2015. Web. http://www.kbwinemarketing.co.nz/wine-news/does-your-wine-marketing-strategy-take-advantage-of-new-media-opportunities-and-target-emerging-wine-consumers/.

Beverland, Michael, Ph.D. “BUILDING ICON WINE BRANDS: EXPLORING THE SYSTEMIC NATURE OF LUXURY WINES.” Department of Marketing, Monash University (Australia), 2010. Abstract. http://academyofwinebusiness.com. May 2010.

Bortolot, Lana. “Wine Label Designs: When What’s on the Outside Matters.” Weblog post. Nomacorc Industry Blog. Nomacorc.com, 19 Oct. 2015. Web. http://www.nomacorc.com/blog/2015/10/wine-label-designs-when-what-is-on-the-outside-matters/.

Bruce, Tom. “TOP 10 MOST POWERFUL FINE WINE BRANDS.” The Drinks Business, 4 Feb. 2015. Web. https://www.thedrinksbusiness.com/2015/02/top-10-most-powerful-fine-wine-brands/.

Dominé, André. “Noble and Mass-Produced Wines.” Wine. N.p.: H.F.Ullmann, 2008. N. pag 116-117. Print.

Dovaz, Michel. Fine Wines: The Best Vintages since 1900. Paris: Assouline, 2009. Print.

Forbes, Sharon, and Dean, David. ” Consumer Perceptions of Wine Brand Names.” 7th AWBR International Conference June 12-15, 2013. Abstract. http://academyofwinebusiness.com. Web. http://academyofwinebusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Forbes-Dean.pdf.

Goode, Jamie. “The Two Cultures: How the Rise of the Brands Is Changing the Face of Wine.” Wine Anorak. N.p., Oct.-Nov. 2002. Web. http://www.wineanorak.com/twocultures.htm.

Haros, Reka. “Wine Branding: Why It’s Important for the Industry’s Growth.” Weblog post. Nomacorc Industry Blog. Nomacorc.com, 24 Nov. 2015. Web. http://www.nomacorc.com/blog/2015/11/wine-branding-why-its-important-for-the-industrys-growth/.

Heine, Klaus, and Francine Espinoza Petersen. “Marketing Lessons Luxury Wine Brands Teach Us About Authenticity and Prestige.” The European Business Review. N.p., 19 Jan. 2015. Web. http://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/?p=6687.

King, Jen. “Younger Affluents with Higher Incomes More Willing to Pay for Fine Wines.” Luxury Daily: The News Leader in Luxury Marketing, 24 Mar. 2016. Web. http://www.luxurydaily.com/younger-affluents-with-higher-incomes-more-willing-to-pay-for-fine-wines/.

Lodge, Alan. “BRANDING NOT IMPORTANT FOR UK WINE CONSUMERS.” The Drinks Business, 15 Feb. 2011. Web. https://www.thedrinksbusiness.com/2011/02/branding-not-important-for-uk-wine-consumers/.

McGechan, Bruce. “6. Creating, Describing and Defining Your Premium Wine Brand.” M&P Wine Marketing. N.p., 21 June 2011. Web. 11 Apr. 2016. http://www.winemarketingpros.com/winery-marketing/creating-your-brand/.

Mora, Pierre. “IS BRANDING AN EFFICIENT TOOL FOR THE WINE INDUSTRY? THREE CASE STUDIES.” International Journal of Case Method Research & Application (2009) XXI, 2. WACRA. Abstract. http://academyofwinebusiness.com. Web. http://www.wacra.org/PublicDomain/IJCRA%20xxi_ii_pg128-139%20Mora.pdf.

“Penfolds Crowned World’s Most Admired Wine Brand – Drinks International – The Global Choice for Drinks Buyers.” Drinks International. N.p., 4 Mar. 2016. Web. http://www.drinksint.com/news/fullstory.php/aid/5934/Penfolds_crowned_World_s_Most_Admired_Wine_Brand.html.

Robinson, Jancis, and Julia Harding, MW. Oxford Companion of Wine, Sept. 2015. Web. 11 Mar. 2016. http://www.jancisrobinson.com/.

Stone, Gabriel. “TOP 10 WINE BRANDS 2015.” The Drinks Business, 7 Apr. 2015. Web. https://www.thedrinksbusiness.com/2015/04/top-10-wine-brands-2015/.

“The Power 100 The World’s Most Powerful Spirits & Wine Brands, 2014.”The Power 100. Intangible Business, 2014. Web. http://www.drinkspowerbrands.com/sites/default/files/downloads/ThePower1002014.pdf.

Townsend, Larry. “The Dramatic Rise of Wine Branding in California.” Weblog post. Owen, Wickersham & Erickson, P.C. N.p., 27 Sept. 2015. Web. 11 Apr. 2016. http://www.owe.com/spotlight/dramatic-rise-wine-branding-california/.

“Wine Buyers Judge Bottles by Their Labels-How Can Brands Stand Out?” Nielsen, 17 Dec. 2015. Web. http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/news/2015/wine-buyers-judge-bottles-by-their-labels-how-can-brands-stand-out.html.